By Keith Clark

Editor’s Note: This interview took place in July 2004.

Jim Long has been a pro audio industry fixture for four decades (and counting), all of it with Electro-Voice (EV), where he recently marked his 40th anniversary. Jim’s long been known for a unique ability to explain audio techniques and concepts in simple, logical and just plain understandable ways.

Don’t believe me? Next time you’re at an NSCA or InfoComm show, drop by the EV booth and take in one his presentations. I guarantee you’ll leave with a better understanding of something you thought you already knew, or learn something you hadn’t ever thought about.

Jim’s still with the company even with its move to Minneapolis, working out of his home office in Southwest Michigan. Full disclosure: you’ve likely seen me talk in about the vital importance of mentoring to our industry, and Jim was my first true mentor in this business when I joined EV in the late 1980s. And whether he realizes it or not, his positive influence on me (and most certainly countless others) continues to this day.

Enjoy the following conversation I had with Jim about his life, work and experiences in our industry.

Keith Clark: How did you get started in this business?

Jim Long: In the early 1960s, I went to Purdue University to get an Electrical Engineering degree, mostly because that’s what my dad expected me to do. In those days, you did that. Prior to summer break in 1963, I decided that I wanted a job, and I was kind of a hi-fi geek. Now, I didn’t think all that much of EV hi-fi speakers, but I knew that EV was not too far from home. So I sent them an e-mail… (laughs).

Actually, after a couple of letters asking for a job went unanswered, I sent them a Western Union telegram. This was a big deal in those days – I had to go to the student union and write it out to be sent. I got a reply pretty quickly, the gist of which was “report to work on June 1” or something to that effect. So I did.

Since then, I’ve never really left EV, except to finish up my degree at Purdue and to get an MBA from Northwestern University. I considered other jobs, and even went to San Francisco to interview with Hewlett Packard, but in the end I took a full-time engineering position with EV. This was in 1966.

KC: So you had a background in engineering. How did you end up in marketing?

JL: Some of this is a bit sketchy in my mind, but I recall that about six months after I took the engineering job, I walked into (EV founder) Al Kahn’s office and inquired about getting into marketing. Al remembers this conversation better than I do – years later he said my words were “keep an eye on me.” But the crux was that I thought I could do more for the company in marketing than in engineering.

So they put me on the distribution list for rep and dealer bulletins, new literature, new-product introductions and the like. Then they asked me to introduce to our reps at a national sales meeting a microphone I’d worked on. This didn’t bother me at all. I had a ball doing it, and it wasn’t long until I was product manager for EV commercial sound.

KC: At that time, what was EV’s status in pro audio?

JL: EV was one of the dominant microphone companies in virtually all applications, and they were also big in hi-fi gear and, to a certain extent, provided commercial sound equipment. I remember seeing a JBL 375 large-format compression driver acting as a doorstop in the engineering department. I didn’t even know what it was. The director of engineering at that time, John Gilliom, explained that it was a professional sound driver and that we (EV) should make them someday.

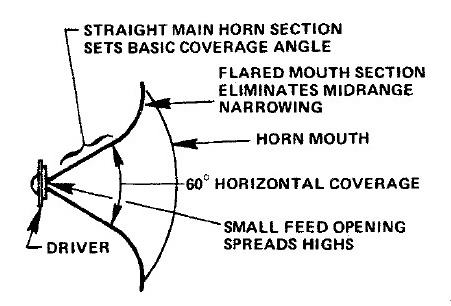

About 1973, John started designing a driver, and horn work was also ongoing, with Don Keele serving as the project engineer on the first constant directivity (CD) horn. The ideas behind constant directivity – maintaining a uniform coverage angle over a wide frequency range – came from John and Ray Newman, as I recall. Don was relatively new to the company at that point, and he took the idea and ran with it, including new and extensive measurements of horn coverage versus frequency, and made the product a reality.

A top section view of a constant directivity horn. Image courtesy of the classic EV Bible publication.

So we ended up with this funny-looking HR series of white fiberglass horns – the first CD horns. The ones I use in the home stereo (one of which is shown with Jim in the image that opens this article) because I’ve never found a better-sounding horn. There were no dedicated low-frequency drivers or enclosures…only box plans for our EVM musical-instrument speakers… and no marketing plan.

KC: So how did you introduce these to the market?

JL: Well, we were going through some pretty lean times at that point, but we had made these horns and drivers, and I remember that (noted consultant) Bob Coffeen liked the light weight of the horns in addition to their constant directivity. So Bob specified HR horns for the Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan – a huge sports arena with an air-supported roof, so the light weight of the horns was a necessity. This got us into the business.

David Klepper and Larry King of Klepper Marshall King also helped a lot by letting us have the 1976 Yankee Stadium renovation project, which they designed. A Bogen contractor won the bid, but they were a commercial sound company and couldn’t buy the Altec and JBL “pro sound” speakers specified.

So we sold them our “line array” – heard that term before? – made up of a huge stack of HR horns mounted in a steel structure above the outfield. There was also a whole bunch of our CDP commercial horns to cover shadowed regions of the main grandstand. It makes sense that these would have been on delay, a very early digital delay, but then again, that doesn’t seem possible given the timeframe. You forget some of the details as the years go by.

The dealer couldn’t equalize the system, didn’t know enough about tuning, didn’t have a spectrum analyzer, had never seen a third-octave graphic EQ, which were still kind of new then. So I, along with some EV technical folks, came out and worked with Larry King on tuning. I don’t even know for sure that we knew exactly what we were doing, but that system was there for a long, long time.

KC: You walked in the door at EV in 1963, and here we are now, 40-plus years later. What’s the biggest change you’ve seen?

Jim: I’m not much of a philosopher. I don’t think the basic way we do business has changed. You need to identify problems that need to be solved and provide solutions, and in the process, build very close relationships with the people who make decisions.

Some of the technology has changed, mostly in the electronics area. The basics of transducers, design wise, were established long before I was born, which was 1941. Sorry, that’s not a very snappy answer, but I believe the core of what we do has remained essentially the same.

KC: What are the most significant products and technologies from EV?

JL: Well, let’s start with EV’s Variable-D directional microphone technology, which eliminated the up-close bass boost of conventional directional mics that “muddies” the voice and reduces intelligibility. That effect is cool for entertainers but is not what you want for the spoken word. There was a time when mics like the EV RE15 and its less expensive brethren were the podium mics of choice, for this reason.

It’s an interesting comment on the industry that the RE15 family is no longer in that premier position, even though we still make one of these mic models. Now you see little condenser mics on podiums, and you get right up on them and they sound “bassy,” with plenty of P-pops. These days people just put up with this, sort of exchanging form for function. It’s like they no longer know how to do it correctly.

Product development is an interesting game, in that you can develop a product for a focused application and that may be where it’s used. An example would be the CD high-frequency horns, which marry several little principles to work extremely well.

On the other hand, I remember the first order of RE20 mics. We had to get 20 of them out to Glen Glenn Sound in Hollywood by a certain day in 1968. Even engraved their name on the mic bodies – it was a big deal. Film sound and production was the expressed primary application of this mic, so it makes sense that Glen Glenn was the first major customer.

But now what’s an RE20 used for? Kick drum, voiceover and radio broadcast. It’s an indication that as hard as Lou Burroughs (Al Kahn’s partner in EV’s predecessor, Radio Engineers, and EV’s “Mr. Microphone”) tried, doing the homework and building the relationships, the product took on a life of its own.

Manifold Technology was a milestone; the idea of combining two to four drivers on one horn with minimum degradation of sound is pretty neat. It got EV into the concert sound business. Then we went to the X-Array systems with [and] Ring Mode Decoupling (RMD), an intensive way of looking for and suppressing the many acoustic and mechanical delayed resonances that color the sound — particularly vocal sound — of loudspeakers.

KC: Why have you hung around so long in the audio business?

JL: I love audio. I’ve never found another industry where the main reason to be in the business – and this can get you in trouble sometimes – is not about making money. We’re not “suits.” We love music, we love reproduction of sound, we love recording. I’m not a performer, but I love listening to high-fidelity reproduction of sound, whether it be in my home or in a sound reinforcement system. It’s my life.

KC: Are you optimistic about the future of the industry?

JL: Yes. Even though the pro audio industry is just a fly on the back of the economy, we’re getting to take advantage of what’s happening in the computer industry. At least they let us use their stuff (laughs).

Jim Long’s been noted as an insightful, engaging presenter whether it was the early ’70s (above) or much more recently.

So there will be convergence – which is just a buzzword – that will continue to happen in a technology sense. We’ll see more and more totally integrated systems that are linked digitally, manipulated digitally, but we’ll have just as much trouble making it work right as anything now.

There will always be a need for people who do good sound, and some folks will chose to do just sound and they’ll do just fine in a business sense. For every big church with a larger production facility than you could have ever imagined 15 years ago, in terms of audio, video, recording, production, duplication, there’s still 100 churches that primarily need just a good PA system. And there will always be a desire for good sound and a general lack of understanding in attaining it. So not everybody will just be able to throw together a sound system with any sort of good or even mediocre results.

KC: I’ve noticed that every generation seems to think that they’ve invented everything truly important to an industry, pretty much ignoring the past. Do you find that to be true as well?

Jim: (laughs) In the early 1960s, EV used to make these things we called line radiators and they were fundamentally stacks of automobile speakers, with some engineering work to give them a unique coverage pattern over a fairly wide bandwidth. That’s still the essence of things like our X-Line and Xlc concert line arrays – the basic concept coming around for at least the second time, with the caveat that they are on steroids in comparison, with tons more engineering.

I probably thought we had invented everything in my generation at one point, but of course, the longer you’re around the more you come to understand that most of the important work has already been done.

A few years ago, Bob Coffeen (a noted consultant) brought a Western Electric compression driver to EV, built in 1935 or so, and the precursor to the JBL 4-inch diaphragm, 2-inch-exit drivers. This driver didn’t have a permanent magnet. Instead, you got the magnetic motor strength by supplying the specified DC current to the field coil.

So we took this driver into the anechoic chamber at EV, bolted it to one of our horns, found a power supply and tenderly put the juice to it, and ran a curve on it. Then we curved the current EV DH1A driver on the same horn. The curves looked exactly the same, except the DH1A went to about 20 kHz, while the Western Electric driver cut out at about 12 kHz.

When you think about that, it’s real humbling. Sure, if you “blasted” the Western Electric driver, it would blow up, but they had come so far at that early stage. By the way, I understand that James Lansing (As in James B Lansing, the founder of JBL) hand-machined the phase plugs for those drivers.

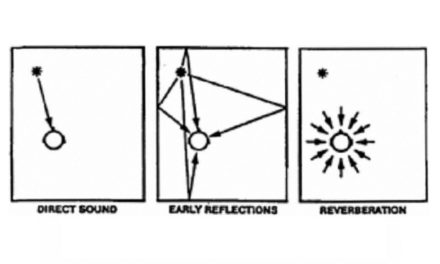

I was privileged to be on hand when Dr. C. P. “Paul” Boner first popularized equalizing a sound system to get the proper response. He was doing parametric EQ before the term was invented, using a 600-ohm mixer and filter bank, looking at the house curve and then working with toroidal inductors made by his friend, Gif White (of White Instruments), putting capacitors across the load to adjust frequency, and then adding resistors to get the right bandwidth.

Thus, the first parametric EQ. Once you got this soldered together, it wasn’t quite as easy as turning a knob to make a change, but he was able to put as many of these filters in as needed to flatten the house curve.

My point is that a lot went on before, which will continue to be the basis of what we do in the future. We’ve had our ups and downs at EV, but boy, it has been interesting.

Related articles:

A Historical Look At EV, With Timeline

The State Of EV In 1953, By Founder Al Kahn