by Kevin Young

If someone had taken Stan Miller aside 40 years ago and told him how much of his career he’d spend on tour with Neil Diamond, he likely wouldn’t have believed it. “I remember driving the bus for a Johnny Cash tour and some members of the band saying they’d played with Johnny for 20 years. I thought, that’s a long time.” Now, however, after over four decades with Diamond. “it actually doesn’t seem that long.”

In all that time, Miller has never missed a gig. When he suffered a heart attack at age 37, Diamond actually postponed a planned tour, insisting on waiting for Miller’s health to improve. “I kept saying ‘yes I can tour,’ and Neil said, ‘give me your doctor’s number.’ Then he called the doctor and took him on tour with us.

“Neil instills loyalty and he is loyal,” Miller continues. “We have some musicians on the road who’ve been in 30 years. I’m 44 years in. I’ve been a very lucky guy.” Diamond is truly a rarity in the business, not only in terms of his dedication to his band and crew, but in his recognition of their value as creative professionals in their own right. “Many artists don’t allow technical people to be creative, and one of the things I’ve enjoyed with Neil was the chance to be creative and to try things.”

Not everything he’s tried was guaranteed to be successful, he continues, referencing a cartoon that depicts him sitting way out on the limb of a tree busily sawing himself a fast way down. “There’s been a few times I was close to falling,” he adds, laughing. Mostly though, he’s done quite the opposite.

Filling A Need

Miller’s career is marked by firsts. He was the first to fly loudspeakers for a touring rig using a system of his own creation, the first to tour with a graphic EQ with third-octave Altec passive filters, the first to use a multi-core snake, the first to pioneer a viable process for applying protective fibreglass coverings to components and road cases – and that’s just a sampling.

His later innovations in the field of digital audio are even more impressive; perhaps chief among them being the first to take a completely digital sound system out on the road shortly after the Yamaha PM1D console was first introduced.

As tempting as it is to portray Miller as the pro audio equivalent of a mad scientist, however, he maintains his accomplishments were more a matter of filling a need than hatching a grand scheme to push live sound technology forward. When he talks about his legacy, it’s with modesty, asserting that everything he’s accomplished is an extension of being a Nebraska farm boy with an irrepressible fascination with machines.

“Necessity is the mother of invention. In those days, we had to invent things. We built our own loudspeakers. We built our own mixers. We built everything but we had to do it the cheapest way possible, and make it work.”

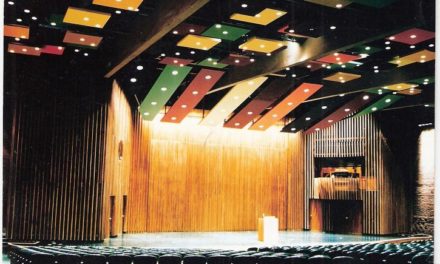

Take the console he built for the live sound of Hot August Night at the Greek Theatre, for example. The album is truly iconic – a defining moment in the development of Diamond’s sound and performance style. “But we were just doing our thing,” Miller says. “At the time, consoles generally had two outputs. We had a string orchestra, and I wanted the strings to envelop Neil’s voice. I needed five outputs and ended up using eight. I played the strings through the rear channels with no delay – I wanted the natural delay.”

New Ways

While Miller insists his innovations are fueled by necessity, there’s very little that makes him happier than figuring out a new way to do something. “If I did things the same way that would be very boring, wouldn’t it? So I’m always looking for new ways to do things; saying how come we can’t do this, or why don’t we do this, or wouldn’t that be cool?”

It’s fair to say Miller is rarely shy about asking those questions or suggesting others pick up a saw, sometimes literally, and find an answer to one of them. As Larry Italia of Yamaha once said, “Stan wasn’t on the cutting edge, he was on the bleeding edge.”

“I remember having a prototype of the Yamaha PM1000-16 at the Universal Amphitheatre,” Miller says, “and talking to Yamaha’s chief engineer at the time, Harry Suzuki. I kept saying ‘Harry, we need more channels. Sixteen is not enough. And he’d say ‘very difficult.’ And I’d say ‘Harry, you cut the end off of one of these, cut the end off another one and then glue them together’.” When Yamaha later rolled out the prototype of the PM1000-32 for a gig Miller was doing in Tokyo at the Budokan ‘that’s essentially what they had done,” he says.

As for what fuels Miller’s drive to innovate? “Toys,” he says, almost sheepishly and laughs again. “Cranes, tractors, grading machines, cars… You have to understand that I like all kinds of machines.”

Charting a Path

Born in Lincoln, Nebraska, and raised in the farming community of Holdrege, Miller had plenty of opportunities to indulge that passion early on. “My father actually started locking the garage because I’d take his tools and scatter them all over the place. I was always building something.”

It was a junior high school music teacher who first introduced him to the basics of loudspeaker building and, after hearing the system he’d helped build in his high school gym, he was hooked. He continued to build loudspeaker boxes, took a gig as a radio announcer (primarily because of the equipment it allowed him to work with) and began to work as a DJ – first at his school and then, after graduating in 1958, at the Sun Valley ski resort in Idaho.

By age 21, he decided he should continue his education and returned to Nebraska to study teaching at Kearney State Teacher’s College (now the University of Nebraska at Kearney). “My parents thought I ought to have a career,” he says by way of explanation, “and there wasn’t any place to go to school to learn audio.”

That didn’t stop him from pursuing his passion. While studying teaching, Miller did sound for college theatre, attended seminars hosted by Altec Lansing’s Don Davis, and in 1962 landed an Altec franchise and started up the small consumer audio store that would eventually become Stanal Sound.

When the college hosted concerts, Miller provided the sound, using Altec’s “Voice of the Theatre” loudspeakers and amplifiers he’d built himself. Through those shows, he developed a relationship with Variety Theater International and began touring with acts like Back Porch Minority, The Smothers Brothers and Peaches and Herb. In 1964, he got his first taste of international touring with The Young Americans in Australia, Thailand and Japan.

Turning a Corner

While these were all wonderful experiences, Miller says, and were important to his development as an engineer/sound designer, it was a gig in Vermillion at the University of South Dakota in 1967 that would have the most dramatic effect on his career. “I was on a bus and truck tour with Peaches and Herb and Neil shared the bill with them. It was a little theatre, 300, maybe 400 people, and Neil’s road manager said ‘geez, that was good. Can you do a show with us in a week or two?’ I said sure, and I’ve never looked back.”

Miller continued to tour with Diamond and countless others while expanding his Nebraska-based audio company – designing and manufacturing the popular Stanley Screamers for Altec, working with JBL as a consultant/designer on their JBL Concert Series, opening an LA office and, ultimately, overseeing upwards of 100 employees. Coordinating all that from the road was difficult because of the limitations of the communications technology of the time, but, even after his heart attack, he refused to slow down.

He also worked at the Greek Theatre and Universal Amphitheatre as a sound contractor and designed systems for Pink Floyd’s The Wall – Live concert in 1981, the opening and closing ceremonies for the 1984 Summer Olympics, and Pope John Paul II’s 1987 appearance at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

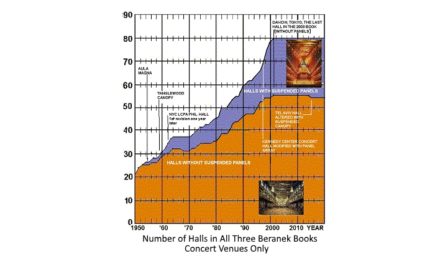

Rather than treat the onset of digital sound technology with skepticism, Miller became a driving force in its advancement – forging a 20-year partnership with Yamaha that led to the development of the PMD1 and PMD5 digital consoles, building a ground-breaking system consisting of 14 small Yamaha digital consoles linked to a computer that allowed recall of settings, pioneering remote control of digital systems and amplifiers, and doing an entire Neil Diamond show using PM1D software and a laptop as his control surface.

As much as he loves technology, however, Miller cautions that a blind dependence on can be counterproductive to innovation. “Some people are so locked in to how they’ve figured out how to do something – not because they figured out a better way to do it – but because somebody else does it that way. The entrepreneurs, the people who own sound companies today, they figured out how to do things that were unusual. That was their niche.”

Basis For Everything

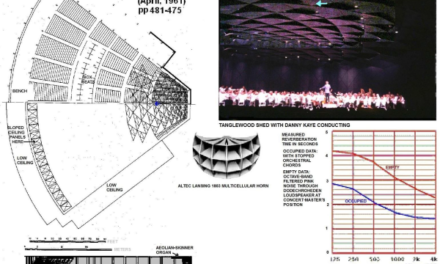

Even when you have an eye on moving forward it’s important to keep an ear on the basics, he says. “Young guys ask me ‘what do I need to do to do what you do?’ And I tell them ‘first, learn to listen.’ I’m a classical music buff. I’m a big believer in listening to acoustic instruments and the acoustics of a room. I think that we have gotten so far in being able to tweak everything we’ve forgotten what some things should sound like.

“Go back to the basics. Go to a concert hall and listen. Get caught up in what’s happening acoustically – that’s the basis for everything – and then use all your tools and tweak the sound.”

As much as his career has been characterized by technology, when asked what he’s most proud of, he takes a much different tack: “That, at 70, I’ve had a fairly full life, that I’ve been lucky enough to have children and grandchildren, and that I have basically been a happy person.” Miller also speaks enthusiastically of the many people he worked with at Stanal who later went on to achieve so much in their own right in audio. “They’re numerous,” he says, “and I’m quite proud of them.”

More than the advances he’s made, more than anything, his relationships with others top the list. Paramount among them, he says, is his ex-wife, Linda, with whom he maintained a close friendship with until her recent passing, his two grown children, and his life partner of 22 years, Thomas Bicanic.

Though Miller sold Stanal in the 1990’s, he only did so when it became an impediment to, rather than an outlet for, innovation. Since, he has continued to push the envelope, ultimately realizing his dream of bringing Diamond’s show to the point of being 100 percent digital on stage and off.

Still Moving Forward

Even after he and Bicanic grew tired of living in LA, relocated full time to the comparatively sleepy town of Big Bear Lake, and purchased the Knickerbocker Mansion in 1998, it’s not as if Miller has slowed down. Although the property had already been converted to a B&B in the 1980s, Miller saw room for improvement. Correspondingly, the two renovated the property extensively, adding new buildings and a restaurant – providing Bicanic a venue for his talents as a chef, and Miller an opportunity to indulge his passion for pairing fine wines with his partner’s creations.

Even with all of the work to be done at the mansion, Miller doesn’t intend to stop touring or innovating any time soon. He remains as excited about audio as ever, and plans to continue exploring the possibilities computer and tablet based control systems offer for the creation of powerful, virtual work surfaces for sound system design and operation.

“As I told Neil some years ago, as long as he keeps going I’ll try to keep up. I tell people, he rocks and I roll.”

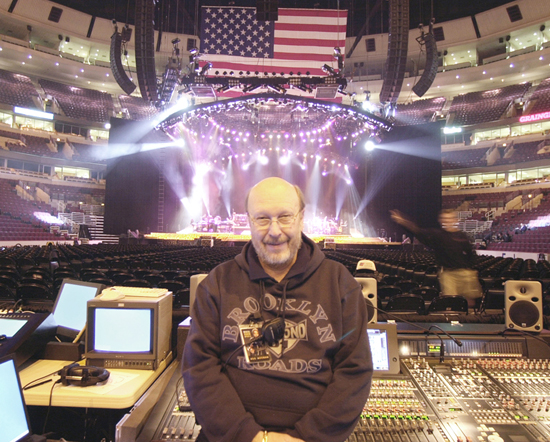

Stan at the Mixing Console

Editor’s Note: A live interview of Stan Miller, recorded at the 2015 NAMM Show, can be found here.

About the Author: Based in Toronto, Kevin Young is a freelance music and tech writer, professional musician and composer.